… “torture” means any act by which severe pain or suffering , whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining … information or a confession, punishing him … intimidating or coercing him … or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official … (article 1 of the UN Convention Against Torture to which the People’s Republic of China is a State Party)

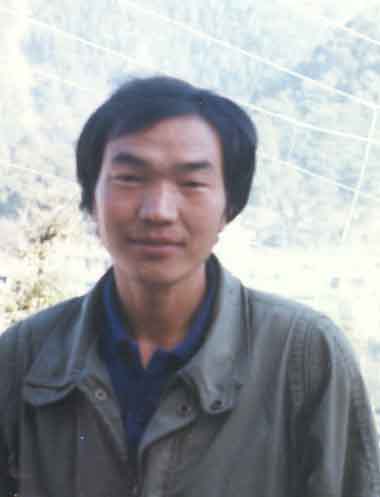

Jampel Tsering (layname – Kalsang), 27, and Ngawang Rinchen (layname – Tashi Delek), 32, are former Drepung monks. They escaped Tibet in October 1996 and were interviewed in Dharamsala, India, in December 1996 by both the TCHRD and a visiting medical delegation from the Physicians for Human Rights, an organisation of health professionals, scientists and citizens based in Boston, USA.

Arrest and detention:

On 27 September 1987, 22 Drepung monks led a demonstration in the Bharkor area of Lhasa. This triggered the massive demonstrations of 1987. Both Jampel Tsering and Ngawang Rinchen were arrested and detained for four months, first in Lhasa’s Gutsa Detention Centre, then transferred to Sangyip Prison from where they were again moved to Gutsa.

On 18 July 1989 a group of Drepung monks including Jampel Tsering and Ngawang Rinchen were arrested for demonstrating in Lhasa. Jampel reports that police came to his monastery and found human rights pamphlets in his room. He was subsequently imprisoned, first at Sangyip Prison and then transferred six months later to Drapchi Prison.

Jampel was sentenced to five years with loss of political rights for three years while Ngawang Rinchen was initially sentenced to nine years, later reduced to six and half years and loss of political rights for five years. (It is once a person is released from prison that he or she faces loss of political rights so a former prisoner is not free in the true sense even after release).

Prison conditions:

According to the two monks, from 1990 to 1992 the political prisoners of Drapchi were required to work for over 10 hours each day although the Chinese authorities claimed that it was only eight hours work each day. The prisoners were put to hard labour without pay, mostly construction and other forms of manual work.

From 1992 onwards the prisoners were required to cultivate vegetable gardens. The authorities expected a maximum produce equivalent to 18,000 yuan and a minimum of 14,000 yuan. If the prisoners failed to raise that amount they were heavily punished for allegedly “avoiding work”.

Working in the plastic enclosed vegetable gardens which were heavily sprayed with pesticides proved very unhealthy for the prisoners. Many prisoners complained of declining eye sight and frequently fainted while working.

Torture:

Upon his arrival at Drapchi Jampel says, “My clothes and personal belongings, including Buddhist scriptures, were burned. I was subsequently beaten mercilessly, repeatedly punched all over my body, including on my face, and kicked in the back.”

He suffered similar severe beatings over the next several days and then less severe beatings almost every day thereafter. He was also shocked with a cattle prod on his face and mouth. During these reports Jampel reports the Chinese guards would say, “You are not allowed to talk about freedom”.

In April 1991, a German human rights group came to the prison. Jampel reports that prior to the visit the Chinese authorities transferred several prisoners suffering torture-related problems out of the prison so that they would not be seen. Jampel says he tried to pass a note to the Germans about the problems in the prisons but it was intercepted by the Chinese officials.

When Jampel and other prisoners demanded to know where the other prisoners had been sent, they were told, “You have no right to ask questions” and were then shackled by their hands and feet bending over. Jampel reports, “I was hit all over my body with fists, I was kicked and I was hit with the butt of a gun”. Jampel and several other prisoners were subsequently taken to very small separate cells without light. He was kept in the cell for 12 days.

Jampel remained imprisoned for a total of five and a half years and reports that, in addition to the physical abuse, he also suffered frequent verbal abuse during his imprisonment. The security guards reportedly told him that “you and your friends are the ones causing trouble in Tibet” and would frequently make derogatory comments about the Dalai Lama.

Jampel reports frequently witnessing other persons being beaten including an old man who he saw being beaten and stepped on. On one occasion, Jampel and some other prisoners brought a fellow prisoner to the prison doctor saying the man was very sick. The doctor reportedly said that there was nothing wrong with the man and sent him away. Five days later the man died.

During his seven years in prison, Ngawang reports that he was tortured severaal times. This included: beatings (kicking, pucnhing, used of sticks, rifle butts and whips); electric cattle prod shocks, prolonged exposure to extreme cold; blood drawing; verbal abuse including death threats to himself, family and freinds, deprivation of sleep, food water toilet and bathing facilities and medical care; solitary confinement for six months from July 18th 1989; forced labour and exercise for prolonged periods without rest and forced standing for prolonged periods of time.

Ngawang currently suffers severe post-traumatic stress disorder and complains of back pains and headache associated with psychological stress.

Ngawang also reports, “There was a very prominent political prisoner, my friend Lhakpa Tsering, who died in 1990 due to a lack of medical care. He was in the cell next to mine and I saw him being tortured”. The two monks report that, in 1994, the prison authorities introduced a new form of torture in the guise of strenuous exercise in addition to even more stringent regulations. Barring meal hours, all prisoners were required to line up and were forcibly made to run from 8.00 am to 12.30 pm and then from 3.00 pm to 6.00 pm.

The same hours applied whether there be hot sun or heavy rain and, according to the two monks, many prisoners became physically weak as a result of these strenuous exercises combined with the poor prison diet.

In one case a monk of Ganden Monastery (layname – Tenzin) was crippled as a result of being made to run forcefully in spite of a knee problem. As Tenzin’s condition worsened, he was given medical leave from the prison as his bills began to accumulate. Today Tenzin has to walk with the help of crutches.

According to the monks, another prisoner, 49-year-old Kalsang Thutop, died the day after he was interrogated for two hours. Kalsang Thutop could not speak after he returned to his cell from the interrogation and later that night he was rushed to the hospital. The next day, 5 July 1996, he died. Kalsang was serving an 18 year sentence for his involvement in the 1989 demonstrations in Lhasa along with the 21 other monks of Drepung Monastery.

Kalsang Thutop was given a sky burial. It was observed by the Topdhen (the person who performs the sky burial) that one of Kalsang’s testicles had been brutally squeezed.

Similarly, the two monks reported that Sangye Tenphel, a 19-year-old monk of Dhamshung Khangmar Monastery, died on 6 May 1996 as a result of severe torture. While in Drapchi Prison, he was beaten up with an electric baton and a cycle pump by two prison officials named Paljor and Penpa. Sangye Tenphel’s ribs were broken during the course of interrogation. He also reportedly suffered from brain damage and showed signs of mental disturbance before his death.

PRC’s adherence to International Law:

Article 11 of the Convention Against Torture specifies that each State Party is to keep under systematic review interrogation rules, instructions, methods and practices as well as arrangements for the custody and treatment of persons subjected to any form of arrest, detention or imprisonment in the territory under its jurisdiction, with a view to preventing any cases of torture.

In 1993 and again in 1996 the UN Committee Against Torture, a team of legal experts, asked China to set up a genuinely independent judiciary and to change its laws to ban all forms of torture. In May 1996 the Committee stated, “there has been a failure to incorporate a definition of torture in China’s domestic legal system in terms consistent with the provisions of the Convention.”

Chinese criminal law only specifically bans torture that is used to extract confessions. Yet in its report to the Committee, the PRC responded that, in China, “the law deems torture to be a criminal act. There is no circumstance that may ever be used to justify its use.”